Sound Design

Goldfish (Jinyu, 金鱼 in Chinese)

2019

Hangzhou, China

The story happens in a future world where the line between male and female is blurred. In a basement/clinic, a doctor and her male patient (who got pregnant but eventually lost his 3 babies) share stories of domestic violence. Both with stories to tell, they agree on a plan to escape the world.

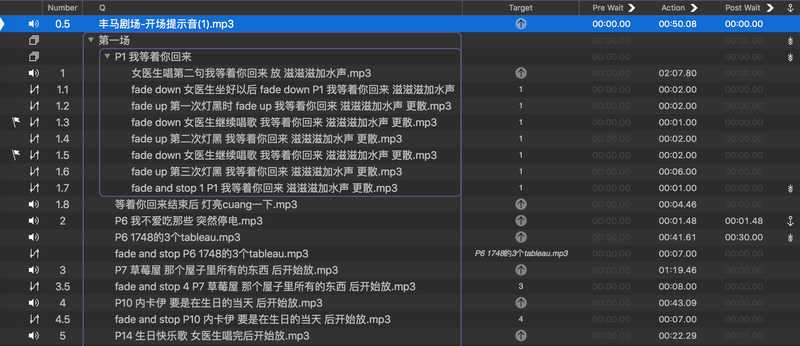

A selection of cues:

I. Sounds with textures

II. Sounds composed with Garageband instruments

III. Sounds with recorded voice

Other files

| |||||||

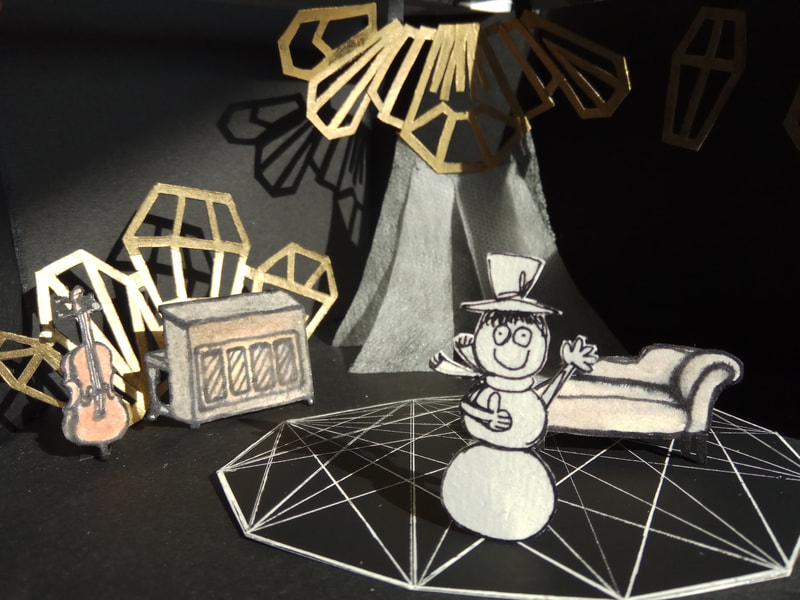

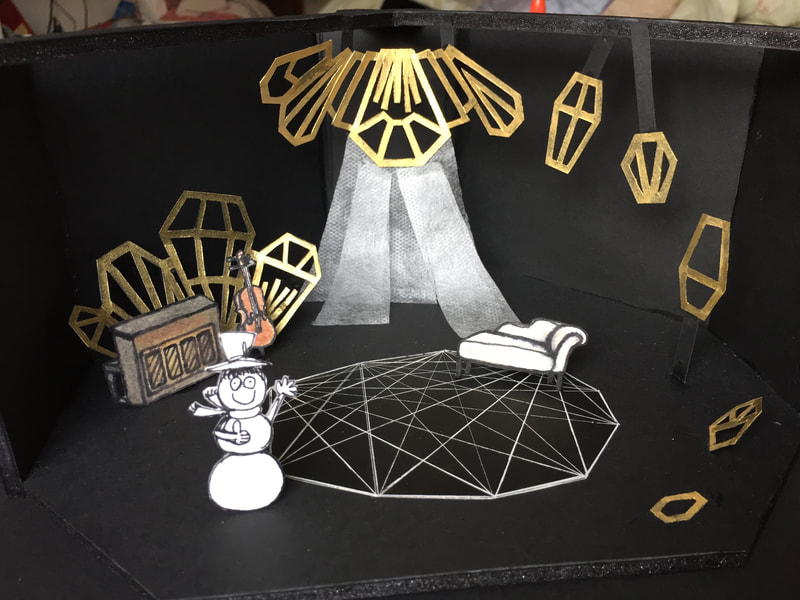

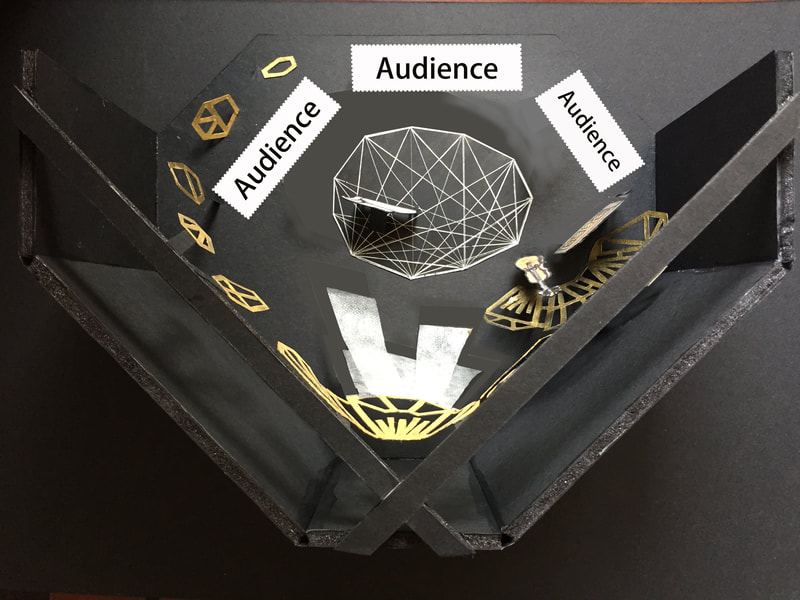

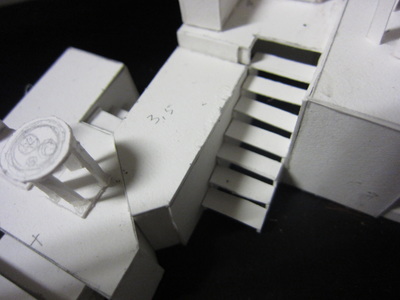

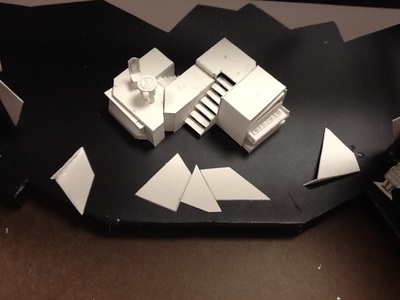

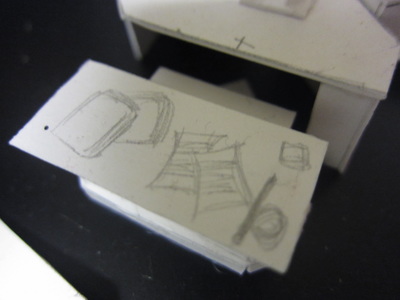

Set Design

Melancholy Play (A Chamber Musical)

2018

Boston University

Sound Design

|

|

Separate cues

|

| ||||||

|

A lame explanation of the thought process, if you wish:

The design ideas for A View from the Bridge derive exclusively from the raw materials - the script and the sound source. For the building blocks of my cues, I combined my own recordings and the virtual instruments in Garageband, merging fiction with reality, since in the world of the play, the private is exposed to the public, and there is no boundary between the real and unreal. Interestingly, sometimes the reality sounds more like fiction. For example, in Cue 7, where the line goes “three flights his head was bouncing like a coconut”, I intended the sound of a working waffle machine to suggest the weight of the content of the lines and the foreboding tension. The recording of this waffle machine ended up so extreme that it sounds like somebody screaming from a cocoon, but with extreme caution. This waffle machine sound is used again in Cue 32, where Eddie and Marco have the final fight and one yells “Anima-a-al!”. Similarly, in Cue 23, I used a recording of me wiping metal bars with paper towel, but with the spices of reverb and echoes, it ended up beastly, which corresponds to the stage direction “They are like animals that have torn at one another and broken up without a decision, each waiting for the other’s mood.”

In this design, sound serves the following circumstances: to evoke atmosphere, to suggest scene changes, to stress or contrast certain words in the lines, and to start and end the acts. For example, when one character walks into darkness, and another comes into the light, I would provide a long cue that ranges between 20 seconds to a minute, hoping to provide a smooth transition between scenes. In Cue 11, I suspended the instruments over a recording of an ongoing rain storm, linking the present with the upcoming trouble that will never go away. In comparison, the cues that responds to specific words from the lines are generally shorter and usually comprises of a single chord. For instance, Cue 5 is only made up of 3 notes, but is simple enough to suggest tension. Cue 13 is made of a chord played arpeggiated, suggesting the anxiety within a person: both smiling and feeling tense. In some cases, sound serves simply as scenic elements. For example, in Cue 12, during the talk between Eddie, Mike, and Louis, I had the recording of traffic and water as the background. During the assembly process, an approach that I often take is to pick a section of the recording and let the instrument imitate one aspect of the recording: the tone, rhythm, or the timbre. During Cue 9, the scene changes from the house to the street. I used the recording of a train with a soft bell sound and had my arpeggiators imitate the ringing of the bell. The combination of bell and train evokes the transition between the domestic and the outdoors. Similarly, in Cue 1, I had the artificial flute imitate the timbre of a fog horn. In Cue 17, I had the instrument first imitate the door creak, and then I varied the pan so that a sense of distrust and awkwardness is revealed. Sound also responds to the objects mentioned in the line. For example, in Cue 4, I overlaid an arpeggiator on top of the recording of clashing screws in order to respond to Eddie’s mentioning of the “clack, clack” sound of the the high heels and heads turning like windmills. I also took an approach opposite from the imitation. In some cases, I had the instrument go against the recording in terms of rhythm and timbre. For example, in Cue 21, the artificial Glockenspiel sounds sweet and mellow at the beginning, but as time progress, it grows syncopated with the recording of heater tapping, which sounds unwelcoming and ruthless. There are different relationships between sound and text. Sometimes the sound speaks directly to the content of the conversation. In Cue 10, in response to the mention of “piers in Italy”, I used the sound of water tapping a plastic board, followed by a touch of woodwind. Sometimes the sound contrasts with what’s offered in the lines, suggesting the absence of things and the emptiness of the environment. In Cue 6, the script says “They continue eating in silence.” But I gave this scene a clock ticking, emphasizing the uneasiness of the situation. In some cases, I had more abstract design decisions, hoping to tap into the psychological world of the character. For example, in Cue 15, in response to the line “I’m a patsy, what can a patsy do?”, I composed a broken chord with artificial harp, growing from on beat to syncopated, so that it indicates self-doubt and helplessness. The overall mood that I want to convey through the tone clusters that I composed is melancholy and self-suspect. In order to achieve this mood, I used three devices: dissonance, legato, and grace notes. Dissonant intervals, usually connected in a legato manner, contribute to a sense of suspension, as if the tones were never supposed to be resolved. For example, in Cue 11, I intended a drastic chord progression. Starting with C-F-A-C, I progressed to D-F-B-D, suggesting the passage of time. But for the third chord I jumped to E-G-B-Eb, an octave above the previous two chords, hopefully indicating the upcoming stormy atmosphere that that’s going to prevail for the rest of the play. Using grace notes is also my way to suggest an unstable state of being. For example, in Cue 28, I used an extremely uneasily sounding pipa, in response to Marco’s spit. On a side note, the grace notes sound like what happens in a medieval chant to me, which bridges the gap between the inner self with the outside environment. I also envisioned instruments from a wide variety of families (as opposed to only woodwinds, or only percussion) Bells are usually associated with lighting changes (e.g. Cues 16, 22). Solo woodwinds are often played with legato (e.g. Cues 5, 30). A lot of the built-in effects in the synthesizer and arpeggiator in Garageband contributed to the conjuration of a realistic atmosphere. For example, in Cue 3, I repeated a group of three notes, descending, and used the Stratosphere effect to suggest a lingering wind that seems never going away. Overall, the sound elements in this design work to their best when they are all messed up, as if about to be blasted by a tornado. |

Productions at Dickinson College

In this production of Charle Mee’s Big Love, I intended to create an otherworldly atmosphere with the sounds that I recorded between 2014 to 2016. These recordings were mostly from my everyday college life in the United States, as well as from my annual brief visits to my hometown Shanghai, China. But when I manipulated the mundane sounds with reverb effects, rate and pitch changes, disturbing sounds formed and went into conversation with the plot of Big Love. For example, throughout long dialogues, I inserted short sound accidents such as the sound of me playing with velcro and zipper, my father patting on comforter, and scene shop workers hanging light bulbs that knocked into each other. For the scenes where the tension gradually built up, I would use more continuous recordings such as the sound of heavy footsteps, museum interior echoes, and the spinning sound of the washing machine.

Other than the use of personal recordings, this production featured a heavy use of reverb and echo effects on speech. Mics were distributed on the stage floor, thus capturing both the actors’ speech and the sound from the speakers, which led to an endless bouncing of mixtures of sound. The echoes brought dimensions to the overall soundscape, creating ethereal sensations unperceivable in the real world. Sound in this production functioned more as an indicator of scene change and mood shift than background music. For example, bells always accompanied Bella’s speeches. But the rate and pitch of the bells varied according to the content of her speech. For example, a faster, higher pitched bell would go with a lighter mood. And a slower, drone-like bell would indicate the serious atmosphere of the scene. There were different types of bells, too, such as wind chimes, ancient Chinese musical instruments, and bells from Plaza de la Constitución in Mexico. At last but not least, the timing of the sound cues was partially improvised. General concepts were established, but each run was different. For example, in the boxing scene, the general idea was to mesh the recordings into a conglomerate of chaos like adding different colors of paint onto the canvas until it became black. When I operated QLab each night, I would let go of the sounds in an arbitrary order instead of a preset one. There was no hierarchy among the sounds of heart beats, car engines, fireworks, chop saw, church organ, or breath intakes, which resulted in a truly chaotic state. This sound design experience to me is less of a theatre production than a conceptual experiment and a sound installation in flux. |

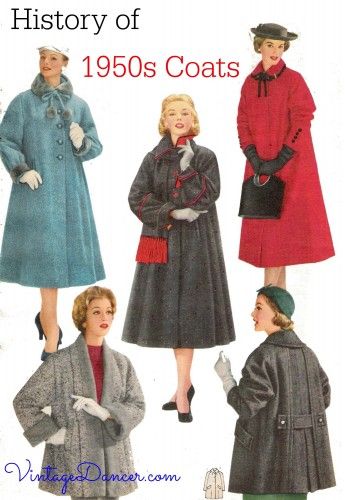

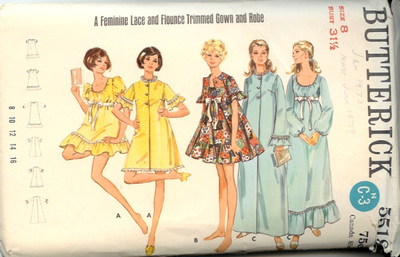

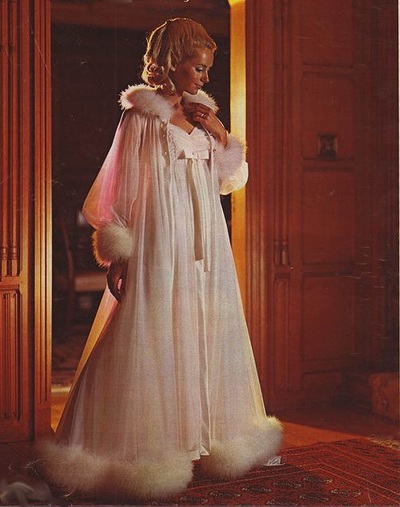

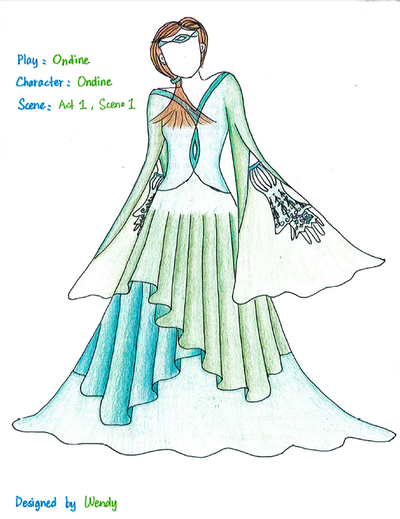

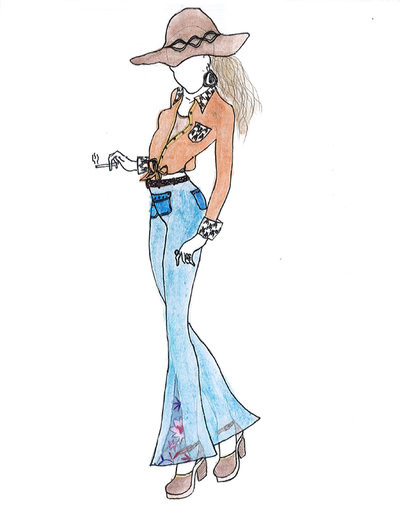

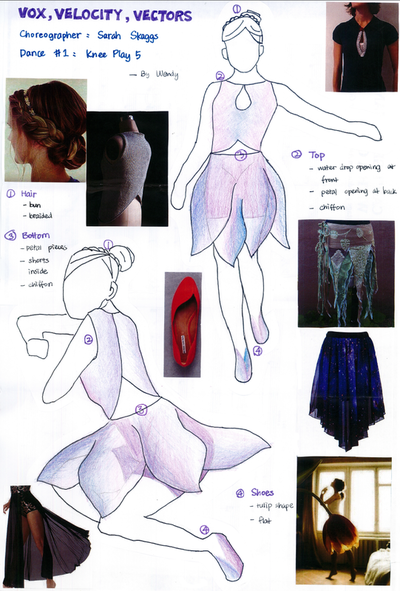

Assistant Costume Design

|

|

Research images | ||||||

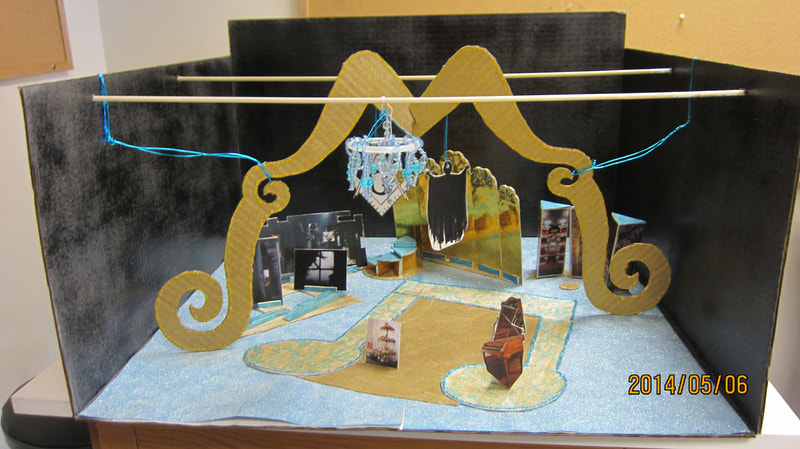

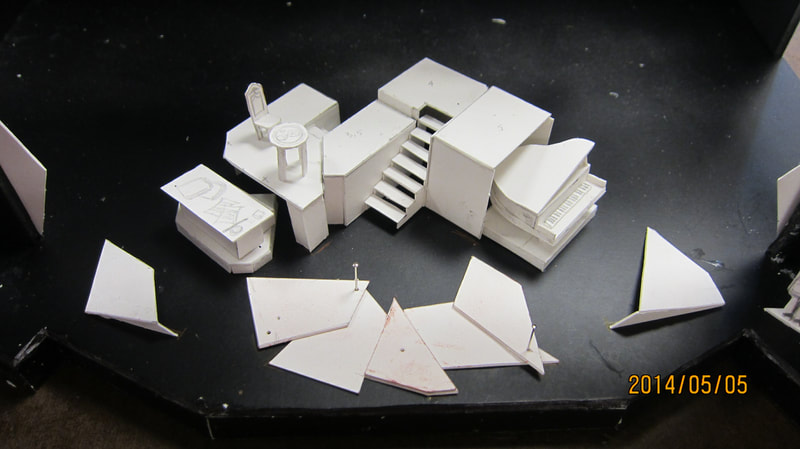

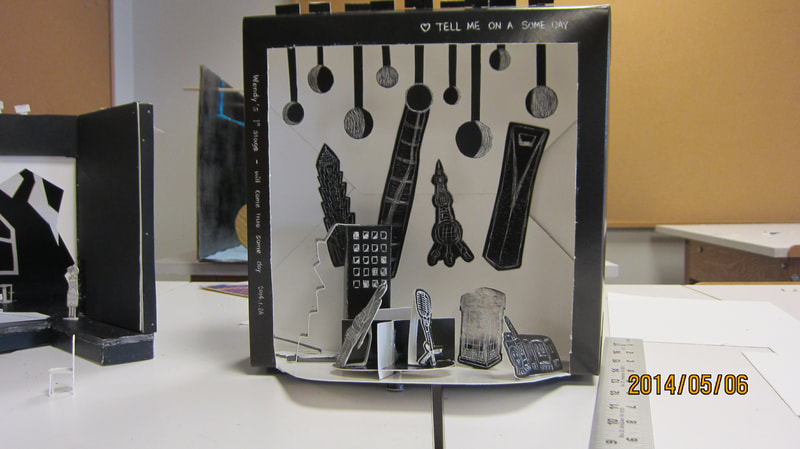

Work from The Scenographic Imagination: Inventing Spaces for Live Performance

| |||||||

| Amadeus Scene Breakdown.pdf | |

| File Size: | 236 kb |

| File Type: | |